Why is California rebuilding in fire country? Because you're paying for it

- Giorgi Nazarov

- Apr 6, 2018

- 7 min read

After last year’s calamity, officials are making the same decisions that put homeowners at risk in the first place.

At the rugged eastern edge of Sonoma County, where new homes have been creeping into the wilderness for decades, Derek Webb barely managed to save his ranch-style resort from the raging fire that swept through the area last October. He spent all night fighting the flames, using shovels and rakes to push the fire back from his property. He was even ready to dive into his pool and breathe through a garden hose if he had to. His neighbors weren’t so daring—or lucky.

On a recent Sunday, Webb wandered through the burnt remains of the ranch next to his. He’s trying to buy the land to build another resort. This doesn’t mean he thinks the area won’t burn again. In fact, he’s sure it will. But he doubts that will deter anyone from rebuilding, least of all him. “Everybody knows that people want to live here,” he says. “Five years from now, you probably won’t even know there was a fire.”

As climate change creates warmer, drier conditions, which increase the risk of fire, California has a chance to rethink how it deals with the problem. Instead, after the state’s worst fire season on record, policymakers appear set to make the same decisions that put homeowners at risk in the first place. Driven by the demands of displaced residents, a housing shortage, and a thriving economy, local officials are issuing permits to rebuild without updating building codes. They’re even exempting residents from zoning rules so they can build bigger homes.

State officials have proposed shielding people in fire-prone areas from increased insurance premiums—potentially at the expense of homeowners elsewhere in California—in an effort to encourage them to remain in areas certain to burn ag

ain. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) spent a record $700 million on fire suppression from July to January, yet last year Governor Jerry Brown suspended the fee that people in fire-prone areas once paid to help offset those costs.

Critics warn that those decisions, however well-intentioned, create perverse incentives that favor the short-term interests of homeowners at the edge of the wilderness—leaving them vulnerable to the next fire while pushing the full cost of risky building decisions onto state and federal taxpayers, firefighters, and insurance companies. “The moral hazard being created is absolutely enormous,” says Ian Adams, a policy analyst at the R Street Institute, which advocates using market signals to address climate risk. “If you want to rebuild in an area where there’s a good chance your home is going to burn down again, go for it. But I don’t want to be subsidizing you.”

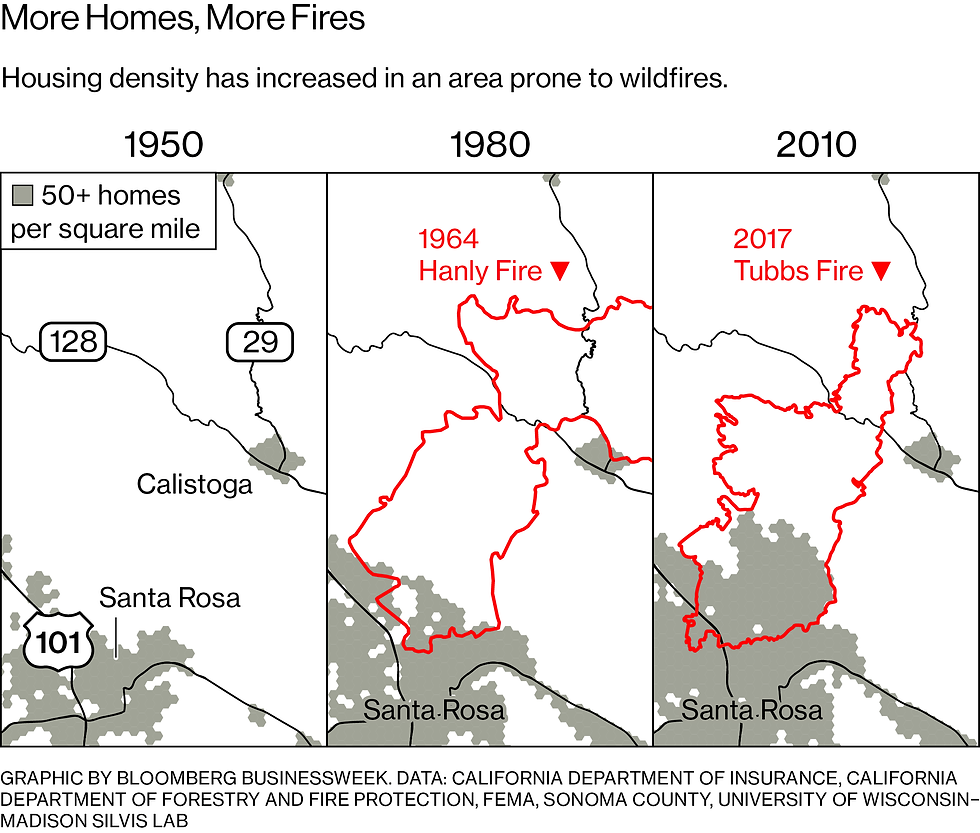

The building boom has vastly increased the potential damages from fire. In 1964 the Hanly Fire in Sonoma County destroyed fewer than 100 homes. Last fall the Tubbs Fire, which covered almost the same ground, destroyed more than 5,000 homes and killed 22 people. And though it was the most destructive, the Tubbs Fire was just one of 131 across California in October. By the end of the year, more than 1 million acres had been burned and 10,000 buildings destroyed.

The next fire may be worse. Sonoma has begun issuing building permits for houses to go back up. Rather than strengthening building codes, the county has weakened rules—passing temporary ordinances that let people expand their homes beyond their previous size and waiving development fees for new units. Other areas hit by fires in 2017, including Anaheim and Ventura, have similarly exempted homeowners from some zoning rules.

Susan Gorin, one of Sonoma’s five elected county supervisors, represents some of the areas hardest hit by the fires. While acknowledging the dangers, Gorin, who lost her own home, says the county has made clear that residents will be allowed to rebuild. “One could make the argument that people were not meant to live in those environments,” she says. But she doesn’t feel it’s her place to make that call. “From my perspective, it is very difficult for governments or anyone to tell another person, another property owner, that they could not, should not, rebuild.”

One of the issues, in Gorin’s view, is fairness: Why should the people whose homes burned be penalized and not those whose homes were spared? “It’s pretty hard to say what is defensible and what is not defensible,” she says. “Are we telling the fire victims that they can’t rebuild, but we’re going to let the other folks remain in place?”

Ray Rasker has been thinking about this issue for years. As a consultant in Montana, he advises governments on how to reduce the damage from wildfires while allowing for development. He says officials’ motive for allowing rebuilding has less to do with fairness than it does with money. “The economics of the West have changed,” he says. Twenty years ago, local budgets came largely from resource extraction, including lumber, oil and gas, and mining. “The new cash cow is homebuilding,” Rasker says. “When they look at a new subdivision, they’re thinking tax revenues. And that clouds their judgment.”

Rasker says part of the problem is perverse incentives: Local officials know that most of the cost of fire suppression and disaster recovery will be paid by state and federal taxpayers. But he warns that putting homes at the forest’s edge costs communities more than they realize. “The suppression cost is about 10 percent of the total,” he says. The rest is harder to see: reduced home values, lost tax revenue, higher insurance costs, closed businesses, even higher medical bills. He estimates half the cost of a wildfire is ultimately borne by the community affected.

Nonetheless, local officials almost always decide that rebuilding makes sense despite the risk that the houses will burn again. Anu Kramer, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, looked at what happened to 3,000 buildings destroyed by wildfires in California from 1970 to 1999. She found that 94 percent were rebuilt. The result is that fires consistently—and predictably—destroy homes in the same place.

“I’ve heard firefighters tell me that they’ve been on the line, and they’d have this eerie sense of déjà vu—they’d think, I’ve been here before,” says Christopher Dicus, a professor of wildland fires and fuels management at California Polytechnic State University. “The key is to avoid building in places that are known fire hazards.”

Nobody illustrates the tension in California’s wildfire policy better than Dave Jones. As a state legislator a decade ago, he introduced a bill requiring local governments to account for fire protection. It was vetoed by then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, who said Cal Fire “should not be in the position of having to act as a local land agency.” As a result, the state fire agency is “now fighting to defend subdivisions in high-risk fire areas that they never had to defend before,” Jones says. “The state has to pick up the cost of that. There’s an externalization of the cost of those decisions.”

Jones has since become California’s insurance commissioner. In January he asked lawmakers for more authority to stop insurers from raising premiums or dropping customers in response to the growing risk. Jones says his position hasn’t changed and that he still supports using local planning and regulation to limit development in fire-prone areas. He just thinks higher premiums are, by contrast, a “crude tool.” The state’s insurance industry, which faces a record $12 billion in claims after last year’s wildfires, warns that tying insurers’ hands will only push costs onto homeowners elsewhere in California. “Of course, people who choose to live in the forest and local governments that continue to approve development in the forest would like less fire-prone areas to subsidize them,” says Rex Frazier, president of the Personal Insurance Federation of California, which represents the industry. “But that just solves one problem by creating another.”

Even attempts at small fixes have failed. In 2011 the legislature levied a fee on people who live in “state responsibility areas”—zones outside cities where the state, rather than local officials, carries the burden of dealing with wildfires. But the fee, which topped out at about $150, proved deeply unpopular among the 800,000 or so households that paid it. Last July the governor scrapped it, replacing the revenue with state funds. Brown’s office declined to comment.

California is just the most obvious example of a national dilemma. In 2013, after 19 firefighters died fighting a wildfire in Arizona, officials in Montana decided it was no longer fair for homeowners to put firefighters at risk by deciding to live at the forest’s edge. The Lewis and Clark Rural Fire Council issued a resolution declaring it wouldn’t go out of its way to save homes in the “Wildland/Urban Interface.” The resolution was written by Sonny Stiger, a retired U.S. Forest Service employee. “There is only one way to say this: No, we are not going to risk our lives to save your house,” he said when the resolution was released. The response from homeowners was swift and furious: Hate email began pouring in almost immediately.

Still, Stiger says, using regulations to keep people from building in dangerous areas is even harder. “When you say ‘zoning regulations,’ people almost come unscrewed.” The only way to produce real change is for the federal government to get stricter about the places it will save from fires, he adds: “The Forest Service is going to have to say, ‘From this date on, we’re not protecting those homes.’ ”

n 2016, Rasker, the Montana consultant, took that message to the Obama administration. Invited to the White House for a meeting about wildfires, he argued that local officials were issuing building permits near national forests and parks knowing that federal forest firefighters were likely to protect them—and pick up the cost. “There’s this disconnect between local land-use authority and what happens when things go wrong,” Rasker recalls saying. He urged officials to seek ways to increase federal grants and other payments to communities that made smart land-use decisions and cut funds for those that didn’t. The White House staff said they agreed with him, Rasker says. Nothing changed.

Tom Harbour was at that meeting as director of the U.S. Forest Service under Obama. He says until local communities get clearer financial signals about the risk of building in vulnerable areas, there’s not much the federal government can do about it. “We’ve designed the system to incentivize and compartmentalize those kinds of behaviors,” he says. “We look only to tomorrow, instead of 10 or 50 years out.”

Back in Sonoma, Kat Geneste, a retired police officer, wanders through the ruins of the house she bought four years ago. October’s fire was the third she’s lived through, she says, and by far the worst. She recalls flames surrounding her car, hearing propane tanks exploding every few seconds, and even seeing animals on fire. At one point, she was certain she’d die. “I kind of kissed my ass goodbye.”

Still, Geneste says she hopes to rebuild her home, then sell it later, once prices recover. Like Webb, she’s not worried that the fires will scare off buyers. If anything, she expects the houses that go up will be even bigger and better than the ones they replace. After what she went through, does she have any advice for people considering whether to live in the area? Yes: “It’s a good time to buy.”

Full Article: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-03-01/why-is-california-rebuilding-in-fire-country-because-you-re-paying-for-it

Comments